The ancient practice of Tai Chi, often described as "meditation in motion," has garnered increasing scientific interest for its potential effects on autonomic nervous system regulation. Emerging research suggests this slow, deliberate movement art may exert profound influence on vagal tone – a key indicator of parasympathetic nervous system activity and overall physiological resilience. Unlike high-intensity exercises that primarily stimulate sympathetic arousal, Tai Chi's unique blend of gentle movement, breath synchronization, and mental focus appears to cultivate vagus nerve activation through multiple synergistic pathways.

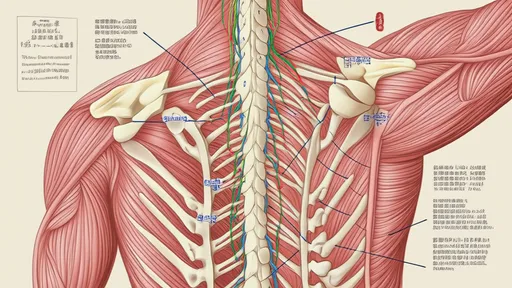

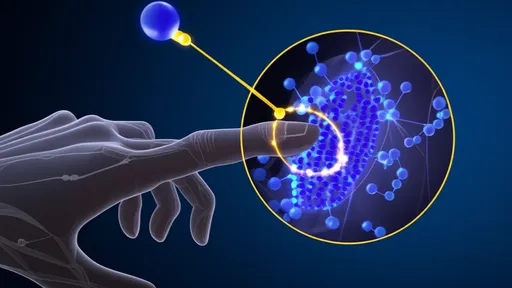

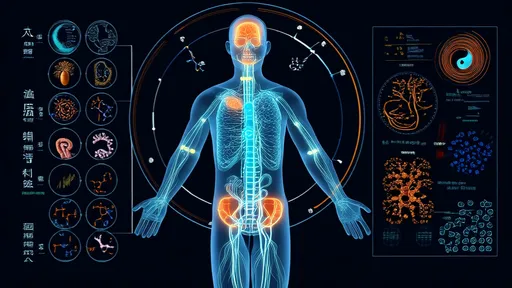

At the neurophysiological level, the vagus nerve serves as the body's information superhighway, carrying bidirectional signals between brain and visceral organs. Vagal tone, typically measured through heart rate variability (HRV), reflects the nervous system's capacity to flexibly adapt to environmental demands. Chronic low vagal tone correlates with inflammation, mood disorders, and cardiovascular risk, while robust vagal activity associates with better emotional regulation and metabolic function. The particular movements in Tai Chi – especially those involving spinal rotation and diaphragmatic breathing – may mechanically stimulate the vagus nerve where it passes through the neck and thorax.

Clinical observations reveal that long-term Tai Chi practitioners often exhibit HRV patterns characteristic of enhanced parasympathetic modulation. A 2022 longitudinal study published in Frontiers in Neuroscience documented significant increases in high-frequency HRV components (a marker of vagal influence) among middle-aged participants after six months of regular practice. Interestingly, these changes were more pronounced than those observed in conventional aerobic exercise groups, suggesting Tai Chi may activate vagal pathways through distinct mechanisms. The researchers hypothesized that the combination of movement precision, breath control, and attentional focus creates a unique neurobiological stimulus.

The respiratory component of Tai Chi appears particularly crucial for vagal modulation. The practice emphasizes slow, abdominal breathing at approximately six cycles per minute – a rhythm that naturally induces resonance between heart rate and breathing patterns. This respiratory sinus arrhythmia represents direct vagus nerve mediation of cardiac function. When synchronized with Tai Chi's flowing movements, this breathing pattern may enhance vagal afferent signaling to brain regions involved in interoception and emotional processing. Neuroimaging studies have detected increased gray matter density in the insula and anterior cingulate cortex among Tai Chi experts, areas densely connected with the vagus nerve.

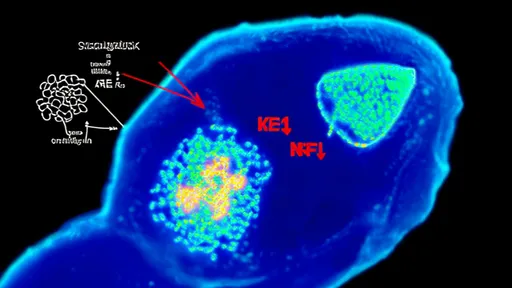

Stress reduction represents another pathway through which Tai Chi may improve vagal tone. Chronic stress depletes parasympathetic reserves through hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis dysregulation. Tai Chi's meditative aspects appear to counter this by reducing cortisol secretion while increasing gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) activity – changes consistently associated with vagus nerve enhancement. The practice's requirement for present-moment awareness may also decrease amygdala reactivity to threats, preventing excessive sympathetic activation that suppresses vagal function.

Practical implications are substantial given the accessibility of Tai Chi across age groups and fitness levels. Unlike pharmacological interventions that target specific receptors, Tai Chi appears to work as a polyvagal regulator, simultaneously addressing multiple physiological systems. Cardiac rehabilitation programs incorporating Tai Chi report faster recovery of autonomic balance post-myocardial infarction compared to standard care. Similarly, studies in type 2 diabetics demonstrate improved glycemic control concurrent with vagal tone enhancement, suggesting interconnected metabolic and neurological benefits.

The depth of Tai Chi's effects may depend on practice quality rather than mere duration. Masters emphasize the importance of song (relaxed alertness) and proper body alignment to facilitate qi (vital energy) flow – concepts that may correspond to optimized biomechanical conditions for vagal activation. Advanced practitioners develop exquisite sensitivity to subtle physiological shifts during practice, possibly reflecting heightened interoceptive awareness mediated by vagal afferents. This mind-body attunement distinguishes Tai Chi from purely mechanical exercises.

While research continues to unravel the precise mechanisms, current evidence positions Tai Chi as a promising vagus nerve training modality. Its integrative approach addresses both the peripheral (body-to-brain) and central (brain-to-body) pathways of vagal communication. As Western medicine increasingly recognizes the importance of parasympathetic resilience in chronic disease prevention, this ancient practice offers a time-tested method for cultivating vagal tone through movement, breath, and mindful presence – without requiring extreme physical exertion or specialized equipment.

By /Jul 14, 2025

By /Jul 14, 2025

By /Jul 14, 2025

By /Jul 14, 2025

By /Jul 14, 2025

By /Jul 14, 2025

By /Jul 14, 2025

By /Jul 14, 2025

By /Jul 14, 2025

By /Jul 14, 2025

By /Jul 14, 2025

By /Jul 14, 2025

By /Jul 14, 2025

By /Jul 14, 2025

By /Jul 14, 2025

By /Jul 14, 2025

By /Jul 14, 2025

By /Jul 14, 2025